Tag: pharmaceutical

S&T to offer pandemic response workshops funded by American Rescue Plan

Missouri University of Science and Technology will offer a three-part workshop series on pandemic preparedness and response this spring.

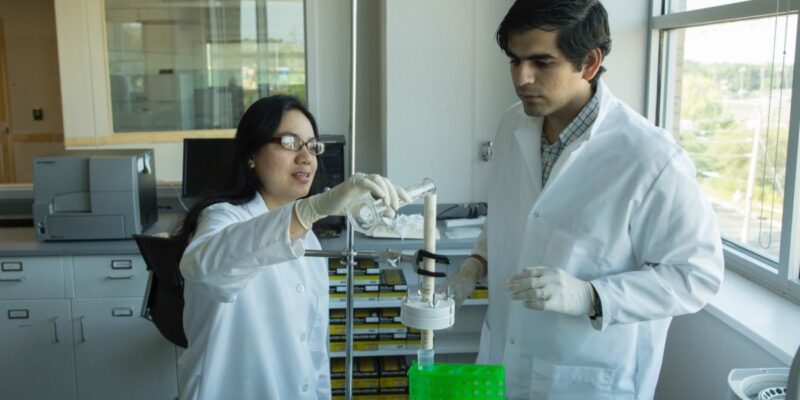

Read More »Missouri S&T biochemical engineer patents low-cost method of removing bacterial toxins from fluids

By some estimates, 18 million people die each year from sepsis triggered by endotoxins – fragments of the outer membranes of bacteria. A biochemical engineer at Missouri S&T has patented a method of removing these harmful elements from water and also from pharmaceutical formulations. Her goal: improve drug safety and increase access to clean drinking water in the developing world.

The technique, as outlined in a July 2016 article in the journal Nanotechnology, involves a one-step phase separation method, using a syringe pump, to synthesize the nanoparticles. Those polymer nanoparticles have a high endotoxin removal efficiency of nearly 1 million endotoxin units per milliliter of water, using only a few micrograms of the material.

Missouri S&T doctoral student works to improve drug safety, efficacy with new chiral templates

In the early 1960s, the Thalidomide drug scare caused thousands of worldwide infant deaths and birth defects from a morning sickness medicine for expectant mothers. The disaster transformed drug regulation systems, and changed the pharmaceutical industry’s understanding of chiral properties: the notion that molecules with otherwise identical properties are in fact mirror images, like your right and left hands. Missouri S&T materials science and engineering doctoral student Meagan Kelso wasn’t even close to being born when the chiral consequences of Thalidomide first became apparent nearly 60 years ago. But the drug industry’s continued efforts to fine-tune how it first identifies and then separates chiral compounds is driving the native Texan’s Ph.D. research.

Read More »Researchers use glass to limit spread of drug-resistant bacteria

As G20 health experts meet this week to discuss the need for new antibiotics to combat drug-resistant bacteria, researchers at Missouri University of Science and Technology are looking to an unusual material – glass – to limit the spread of drug-resistant bugs in humans.

Read More »Chemical transport in plants likened to that of humans

Plant roots and certain human membrane systems resist chemical transport in much the same way, say researchers at Missouri University of Science and Technology in a recent journal article. This similarity could make it easier to assess chemical risks for both people and plants, and may even lead to a new approach to testing medications.

Read More »