S&T lab partners with top electronics companies, military agencies for EMC research

Posted by Greg Edwards

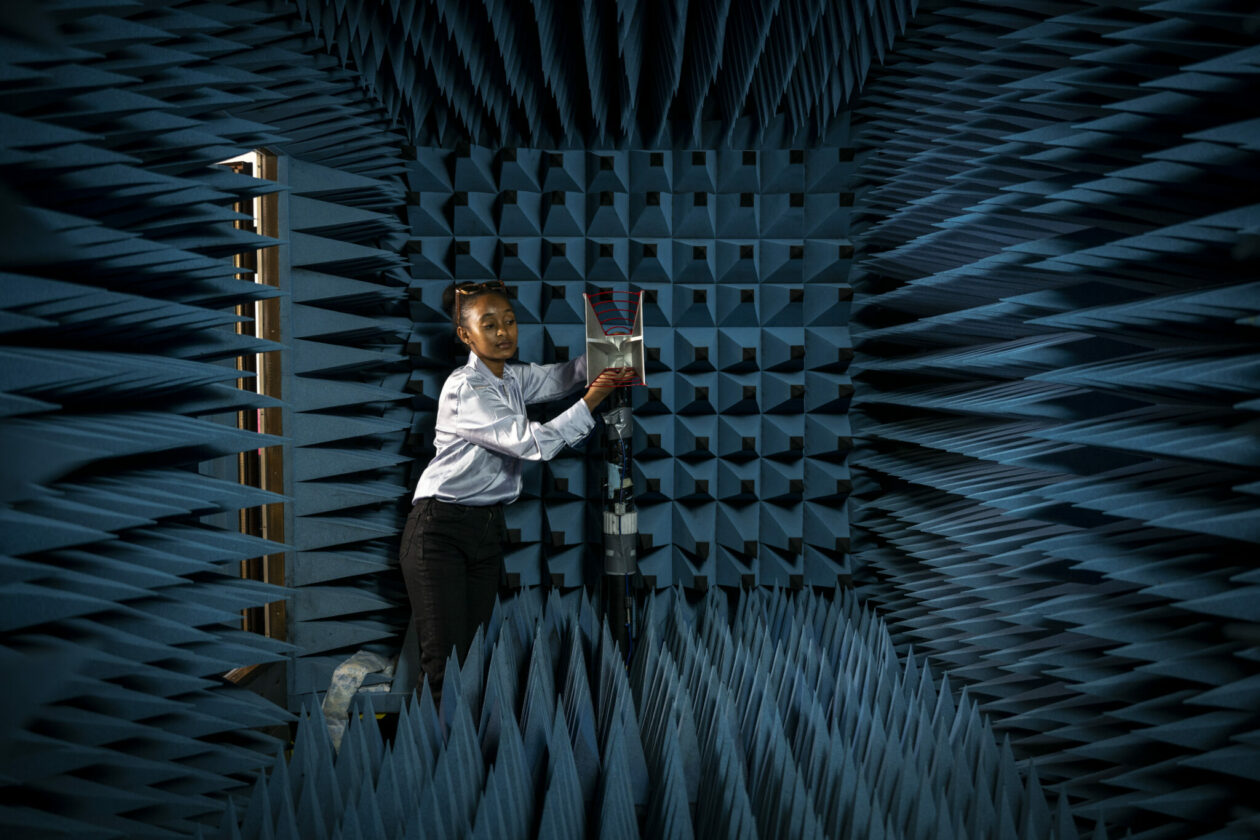

S&T student Kalkidan Anjajo, of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, sets up a horn antenna to make antenna pattern measurements in an anechoic chamber. Anjajo is a master’s student in S&T’s electrical engineering department. Photo by Michael Pierce/Missouri S&T.

Missouri S&T has a longstanding reputation as a top-tier STEM school, but anyone unfamiliar with the university’s Electromagnetic Compatibility (EMC) Laboratory would likely be shocked by the level of influence the university has globally on consumer and military electronics.

“It would be impossible to guess the number of products that are affected by our lab,” says Dr. Daryl Beetner, an electrical engineering professor who serves as director of the lab. “When you consider the number of companies we work with, coupled with the large number of alumni we have in industry, our lab has an enormous impact on the electronics field.”

Companies need Missouri S&T’s capabilities in part because the Federal Communications Commission limits the amount of unintended electromagnetic emissions, or noise, that can be emitted from devices. Beetner says that measuring the amount of noise and then finding ways to reduce noise levels requires a lot of math and hands-on experiments, and this is not simple research to conduct.

Enter Missouri S&T’s EMC Lab, which is the largest university-based EMC lab of its kind in the world. Missouri S&T’s $10 million-plus facility has a multi-million-dollar annual operating budget and houses four full-time faculty members, 40 students, two to four postdoctoral fellows, a laboratory technician, and support staff.

The EMC Lab leads the Center for Electromagnetic Compatibility, an industry consortium sponsoring EMC research that includes Apple, Intel, Google, Cisco, Samsung, LG, Amazon, Facebook, IBM and several other leading technology companies around the world among its membership.

The center is a National Science Foundation Industry/University Cooperative Research Center.

S&T also has several other partnerships in industry and U.S. government, such as the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the Office of Naval Research and Hyundai Mobis, among others.

“We help our partners find better ways to tackle problems with unintended emissions, electromagnetic immunity and signal integrity,” Beetner says. “It’s extraordinarily challenging to make electronic systems that don’t emit too much noise, aren’t susceptible to electromagnetic energy, and can achieve the communications speeds required in modern digital systems, while also meeting all the other requirements with respect to size, cost, performance, and so forth.”

“Companies come to us for help because we have substantial experience with these issues and the capability to investigate and solve them,” he says.

In terms of federal research, the EMC lab also focuses on the susceptibility of electronics to electromagnetic energy.

“For national defense purposes, it can be useful to know how to disrupt adversaries’ electronics, while also understanding how they could potentially interfere with ours,” Beetner says.

The S&T facility features chambers that block outside interference when researchers test devices. It also houses state-of-the art instruments, such as a 50 GHz vector network analyzer, a 50 GHz spectrum analyzer, large experimental work areas, and micro-probing stations.

Since 2008, the EMC lab has been housed in a 15,000-square-foot facility located about 4.5 miles from S&T’s main campus.

The building, which neighbors a gas station and an egg carton manufacturing facility, may seem unassuming, but the work conducted inside its doors is anything but.

“Digital electronics play such a big part in our daily lives,” Beetner says. “People know the names of the companies that produce these products, but they probably don’t know that Missouri S&T often plays a behind-the-scenes role in their development. We’re proud of the impact we’re making on the world.”

For more information about Missouri S&T’s EMC lab, visit emclab.mst.edu.

About Missouri S&T

Missouri University of Science and Technology (Missouri S&T) is a STEM-focused research university of over 7,000 students. Part of the four-campus University of Missouri System and located in Rolla, Missouri, Missouri S&T offers 101 degrees in 40 areas of study and is among the nation’s top 10 universities for return on investment, according to Business Insider. For more information about Missouri S&T, visit www.mst.edu.

I have read of the Carrington Event of 1859. The damage that occurred was not significant because there were few electrical devices. With the electrical network and devices we have now, it would be disastrous. This was rare; but it may happen in the future. While studying electromagnetic emissions perhaps we should look at how to protect devices and the electrical network from another such event or an electromagnetic pulse from and enemy

Nice article about an important industrial capability at S&T. However, in the third paragraph it states that the “Federal Trade Commission” places limits on the levels of unintended RF emissions from devices. I seriously doubt the FTC has a strong regulatory role here. On the other hand, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) does indeed have a very strong interest in regulating RF emissions (both intended and unintended). I suspect this is the correct government agency which should be referenced in the text.

Thanks, Wayne! Great catch. The article has been updated.