The doctor is IN

Posted by Peter Ehrhard

Dr. David Westenberg works in the lab at 203 Schrenk Hall. Westenberg estimates he has taught every S&T student who has gone on to med school over the past 15 years. Photos by Sam O’Keefe/Missouri S&T

“The medical students from Rolla are different. Every single one seems to be scarily talented and driven.”

That is the opinion of Dave Westenberg, who says he has probably taught a class to every S&T student who has gone on to medical school in the past 15 years. “It makes writing letters of recommendation for medical schools really easy, though,” he notes.

Every year, undergraduate students from colleges and universities around the nation apply to medical schools. But what makes Missouri S&T’s five-to-10 annual applicants stand out is their background. Every medical student is smart and studious, but what they may lack is S&T’s hands-on training in subjects outside of medicine.

“We want our students to be well-rounded and prepared for a number of careers,” says Westenberg, an associate professor of biological sciences who just concluded a term as interim chair of the department. “You cannot get a job in pre-medicine. That is why we do not offer it as a major. Instead, we teach them skills in biology, chemistry, psychology and engineering, not a strict focus on medical application-only lessons.”

Missouri S&T has a pre-med program, but it is more there for guidance and support, says Westenberg. Missouri S&T students get into medical school through their own merit, rather than following a pre-established pipeline.

Students applying to medical schools still need to take classes in the sciences, such as genetics and cell biology, but there is less focus on quantity and more on quality.

“In the past few decades, there has been a shift in what makes a good medical student,” says Alice Arredondo, assistant dean of admissions and recruitment at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine. “Strong applicants are well-rounded individuals who also exhibit teamwork and communication skills. Admissions committees will accept students based on their potential to contribute to the future of the medical field, not just because they had a high GPA.”

Real-world application

Dr. Karlynn Sievers, who earned a bachelor of science degree in life sciences and a bachelor of arts degree in English in 1996 from Missouri S&T, is proof that the path to medical school is not always straight-forward.

“I wasn’t one of those people who wanted to be a doctor since kindergarten,” says Sievers, a family practitioner and faculty member at St. Mary’s Regional Medical Center in Grand Junction, Colo., where she teaches medical residents. “I originally wanted to be a technical writer, but found research projects in chemistry and biology to be a lot of fun.”

After deciding to apply for medical school, Sievers worried about the lack of anatomy studies that many traditional medical school applicants have. But her concerns were unfounded, as she discovered that medical schools demanded a more well-rounded student than typically assumed.

“Medical school requires a strong science background, which I had from life sciences, but application boards also want intangibles,” says Sievers. “I credit my confidence, leadership and communication skills from Kappa Delta sorority participation for my successful application — those are the types of characteristics a medical professional really needs to thrive.”

Dr. Karlyn Sievers sees patients as a family medicine physician and teaches residents as a faculty member at St. Mary’s Regional Medical Center in Grand Junction, Colo. Telluride Wedding Photographer, Cat Mayer Studio

After being frustrated in her first engineering course at S&T, Dr. Christina Byron, who earned a bachelor of science degree in chemistry in 2003 from Missouri S&T, an OB/GYN at Mercy Clinic in O’Fallon, Mo., and Ballwin, Mo., decided to change majors. It was the best career decision she ever made.

“Medicine and engineering have a number of parallels; it just depends on how you want to learn,” says Byron. “Medicine is like fixing a car, only you are working with a human body. You ask questions, test parts and then repair; it is more about having problem-solving abilities rather than any one particular skill set.”

Dr. Christina Byron is an OB/GYN at Mercy Women’s Health in O’Fallon. Photos by Sam O’Keefe/Missouri S&T

Engineering a minor

“It doesn’t solely matter what subject a student studies, their age or previous work, I have seen many different types get accepted to medical school,” says Julie Semon, an assistant professor of biological sciences at Missouri S&T who coordinates the university’s introduction to biomedical engineering course. “That is what trips up some students. It’s not just grades or studies, but experiences and hands-on learning, which we offer in abundance.

“For example, one day a student in my lab was examining a sample through a microscope and saw our mesenchymal stem cells ‘eating’ bioactive-glass pieces used in an experimental treatment,” Semon says. “After he asked me why they do that, I told him that nobody knows, as he was probably the first person in the world to ever witness that phenomena. And that type of experience is what sets S&T students apart in the application process.”

The biomedical engineering minor, in its second year at S&T, often involves interdisciplinary research for its students.

Semon teaches tissue engineering and stem cell biology, but professors from chemical engineering, ceramic engineering, chemistry, electrical engineering and mechanical engineering also teach courses.

“It gives our students more perspective,” says Semon. “Biologists approach problems in a similar manner even when working on different projects, like applying the scientific process to fungal research or biomedical problems. Engineers, on the other hand, have different approaches to problems than biologists.”

While only a few students in the biomedical engineering minor plan to go on to medical school, they all learn the do’s and don’ts of medical research.

“For our pre-med students, we don’t focus so much on getting into medical school,” says Semon. “We are more worried about how they will manage once they are out in the world. Society tends to put doctors on a pedestal, but we want to make sure S&T graduates deserve to be up there.”

Julie Semon, an assistant professor or biological sciences at Missouri S&T, coordinates the introduction to biomedical engineering course. Sam O’Keefe/Missouri S&T

Brainstorming a solution

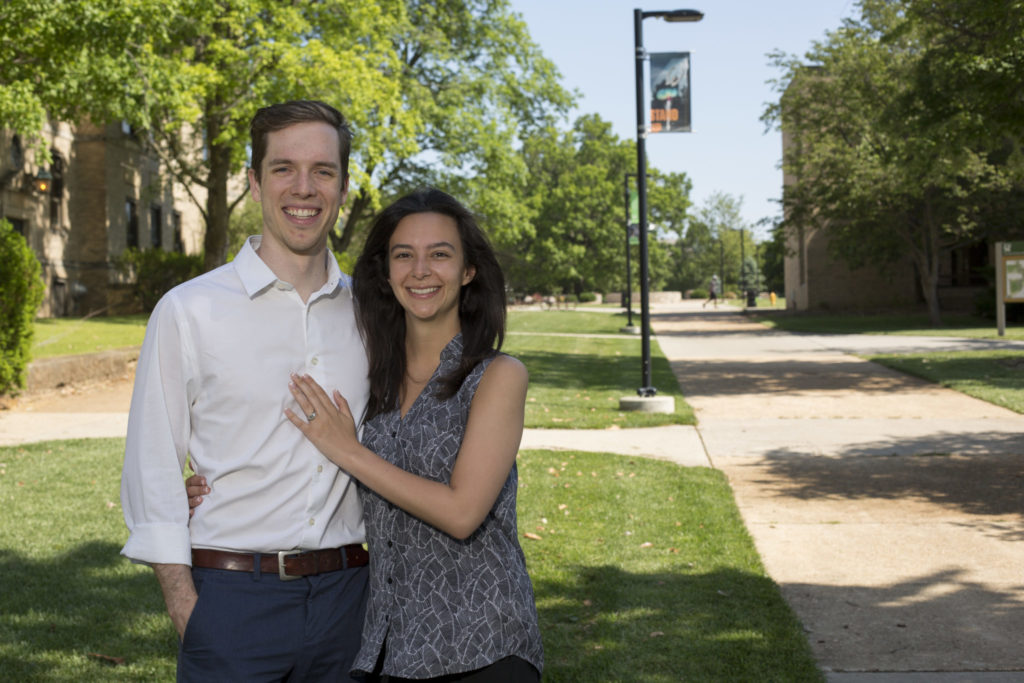

Robert Adams, a 2010 mechanical engineering graduate from Missouri S&T, and Dr. Selin Acar, a 2012 chemistry graduate from S&T, are a husband-and-wife duo finishing up medical training. Adams is a seventh-year combined Ph.D. and M.D. student at Saint Louis University focused on neurological studies. Acar is a first-year psychiatry resident at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. Adams will soon join Acar in Cleveland to work at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, a part of Case Western Reserve University. Both have S&T faculty connections — Acar’s father is electrical engineering professor Levent Acar, and Adams’ father is the former John and Susan Mathes Chair in Environmental Engineering, who now works at SLU.

The two are the yin and yang of both medical school preparation and brain studies.

“Medical school is particularly rigorous, and I didn’t have much anatomy background,” says Acar. “Luckily, though medical school is tough, there is always a lot of support along the way. My time at S&T really shaped the way I think and approach problems.”

“I believe being from outside the traditional majors for pre-meds helps me look at problems differently and contribute from a unique angle,” says Adams. “This is especially true when it comes to engineering-style problems like bone stresses or blood pumping issues.”

Dr. Selin Acar is a psychiatry resident at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. Her husband, Robert Adams, is finishing studies in neurology at Saint Louis University. Photos by Sam O’Keefe/Missouri S&T

Oh the places you’ll go

So if S&T students transition so smoothly into the medical profession, why don’t we have more alumni doctors?

“The biggest reason we don’t have more students go on to medical school is that they are almost too skilled and end up graduating with a ton of career choices,” says Westenberg. “More could go on to practice medicine, but they can also go on to be an engineer, technical writer, researcher or scientist instead. It all comes down to what our graduates put their mind to.”

I knew Dr. Sievers would do great, as she was growing up in Kansas City at the church I grew up. I was delighted and excited when she said she was going to Rolla. Excellent choice as a launching pad for medical school and medical practice.

Loved this article! Great to see how different students used their undergraduate education as a foundation to pursue some fantastic careers in medicine.