AI will change your future

Posted by Peter Ehrhard

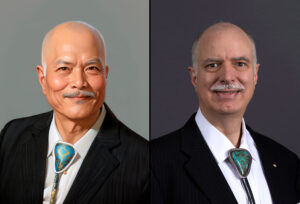

Joe Miner (left) with an artificial intelligence-generated image of his physical description on the right.

Artificial intelligence is here to stay, along with all its controversies, questions and ambiguity. It is rising in the workplace and changing the way we work. Many researchers have looked at potential downsides, but few have looked at the upsides.

We interviewed three Missouri S&T faculty members with expertise in different academic disciplines and asked them about AI’s future, how accepted it is by the general public, how it will interplay with the economy and the ethical implications of its use.

The economy will be affected

The consensus among Missouri S&T experts is that, while the economy will change, disruptions will be counterbalanced by new opportunities.

“AI will not gain the general human capabilities within 20 years,” says Dr. Donald Wunsch, director of the Kummer Institute Center for Artificial Intelligence and Autonomous Systems and the Mary Finley Professor of electrical and computer engineering at S&T. “There will continue to be workforce changes, in blue- and white-collar positions. Certain current low-paid jobs will become much more valuable, and other six-or-seven figure jobs may be taken over by AI. For example, future AI can achieve higher performance than a hedge fund manager. But people won’t trust an AI babysitter.”

Dr. Daniel Shank, an associate professor of psychological science at S&T, echoed Wunsch’s opinion.

“I’m not convinced that mass layoffs due to AI are likely, even industry-wide ones, at least in the near future,” says Shank. “AI is good at supplementing processes and automating boring parts of tasks, but as it has done so industries adapt – finding different uses for humans versus AI.”

Writing, music, movies and art – traditional humanities fields – are the ones often featured in the media when it comes to AI producing and creating. Many fear that these areas will be reduced to little interaction from humans. But work will continue as it always has, just in different and new ways.

“Chatbots and large language models are an incredible development, and we are only at the beginning of seeing what can happen with it,” says Dr. Darin Finke, teaching professor of philosophy at Missouri S&T. “But the history of AI is a history of over-hyping. Every time there appears to be a new technological breakthrough concerning AI, the exaggerated predictions follow.”

How soon will you work with AI?

One day, the technology may eventually grow to the point that it can provide many functions in society. Are there any industries that are safe, such as teaching, medicine, hairstyling or plumbing? Would people be accepting of working or interacting alongside a fully AI co-worker in a chatbot role, a graphic designer or a taxi driver?

“I don’t think most people have experiences with AIs or robots as coworkers,” says Shank. “Even when AIs and robots take human jobs, people tend to see them as tools or as ways to augment their own work.”

Shank says that there are still, even today, some tasks that AI or robots can do much better than humans, but humans continue to do them.

“In terms of automated systems, especially when there are options for humans or machines, both the wide acceptance, performance and personal preferences come into play,” says Shank. “So there might be a base level of acceptance or preference, so the same person might be terrified to ride in an autonomous vehicle but also rather talk to a chatbot about a banking issue.

“In some industries, there might be cases of sudden shifts shaking up employment arrangements,” Shank continues. “For example, automated vehicles and human taxi drivers is a case where a lot of conflict is being seen, including legal issues.”

Wunsch also believes that the time when individual robots can replace an individual person is still far off.

“If all drivers were AI, the problem would be much easier, because humans are bad drivers. But people won’t accept that. I would accept a driverless car moving slowly in a predictable environment, like a golf cart or certain factories – but not on typical roadways,” says Wunsch. “The main problem is with unpredictability. The general principle applies – the more carefully a problem can be specified, the more likely an AI solution might be helpful; and that still leaves a lot of room to apply AI.”

Can we ethically shape AI use?

Could human-to-human interaction in general potentially become rarer in the future? Or maybe the opposite will happen, because with more time and tasks eased, perhaps individuals will be allowed to put more time and effort into volunteerism or other fulfilling activities. Jobs will always exist, but the workplace, job market and whole industries may one day change beyond recognition.

“For years now, organizational task-only human-to-human interaction has been decreasing,” says Shank. “We don’t have to have people for every financial transaction and for every service. There are consequences to not having long-term exposure to people in different transactional arenas like fast food. But people’s meaningful personal relationships are much more important to maintain than their exposure to human fast-food servers.”

The impact on jobs could lead to a question of ethics on new scales, Finke says. “New technology will always be slightly ahead of the ethics related to that technology,” says Finke. “And then the ethicists try to play catch-up.”

So how does ethics connect to the world of AI? Often, history has the answer – with a similar panic happening during the industrialization of farming and large-scale machine work. Modern questions may be more along the lines of if an AI-generated piece of art can be “owned,” or if someone would allow AI to teach their child in a classroom.

“With the rise of digital technology over the past two decades, many philosophy programs across the country have responded by developing courses and degrees specifically related to digital and AI ethics, which are relatively new fields,” says Finke. “The next steps not only include further developing digital and AI ethics, but also figuring out, or framing, other non-ethical issues related to that technology.

“For instance, can the output of ChatGPT be original? Can it really be creative? Who owns that output? Can it be copyrighted?” Finke asks. “AI technology is already being used in art and photography competitions, so questions of authorship and creativity, and even legality, seem to arise when writers or artists or poets or academics, or whoever, utilize AI in their works.”

A new cold war

Another aspect of the future of AI is the disparity between countries’ economies. Would a lack of infrastructure affect growth in certain areas of the world? Could AI lessen the gap between the world’s rich and poor or could it worsen it?

“AI will bring us closer to either utopia or dystopia, and the decisions we make now will influence on which outcome is achieved,” says Wunsch. “We need to be responsive to the extraordinary level of international competition in AI”

If governments take a more passive role in AI use or development, then it may fall to companies to battle for the commanding heights of the economy. Perhaps there will be new major tech companies emerging, or the current large companies growing along with AI.

“The arms races with AI are more company-based than country-based, and countries seem to be struggling to keep up in terms of laws, taxes, trade agreements and policies to guide the ethical use of AI,” says Shank. “On the other hand, there is some uneven distribution.”

Shank says that only a handful of companies in the world can train the most advanced AI large-language models that use statistical models to analyze and understand text like the currently popular ChatGPT. But once trained it can be distributed and integrated into products easily and used by people anywhere.

As for a race to the top, Wunsch agrees that it has already started and could continue to escalate.

“AI growth between countries will remain a race,” says Wunsch. “There will still be a lot of room for innovation from unpredictable sources, particularly in the mathematics of AI.”

Wunsch also says that he believes that the political and economic impacts of AI will be tremendous. He hopes that political leaders reach out to the subject matter experts instead of listening to all the noise about AI – some of which is even produced by AI itself.

“Stakes are high, with much pressure for regulation, some of which is misaligned with actual AI opportunities and threats. Our leaders must seek expert input that is aligned with constituents’ interests,” says Wunsch. “Many coastal AI experts influencing policy miss key issues that affect diverse elements of society and opportunities for disruptive innovation. In some cases, they prefer to suppress it. And expert opinions differ widely, thus the need to seek local viewpoints.”

About Missouri S&T

Missouri University of Science and Technology (Missouri S&T) is a STEM-focused research university of over 7,000 students located in Rolla, Missouri. Part of the four-campus University of Missouri System, Missouri S&T offers over 100 degrees in 40 areas of study and is among the nation’s top public universities for salary impact, according to the Wall Street Journal. For more information about Missouri S&T, visit www.mst.edu.

Leave a Reply