Missouri S&T joins LIGO and Virgo’s newest research on neutron star smash-ups

Posted by Delia Croessmann

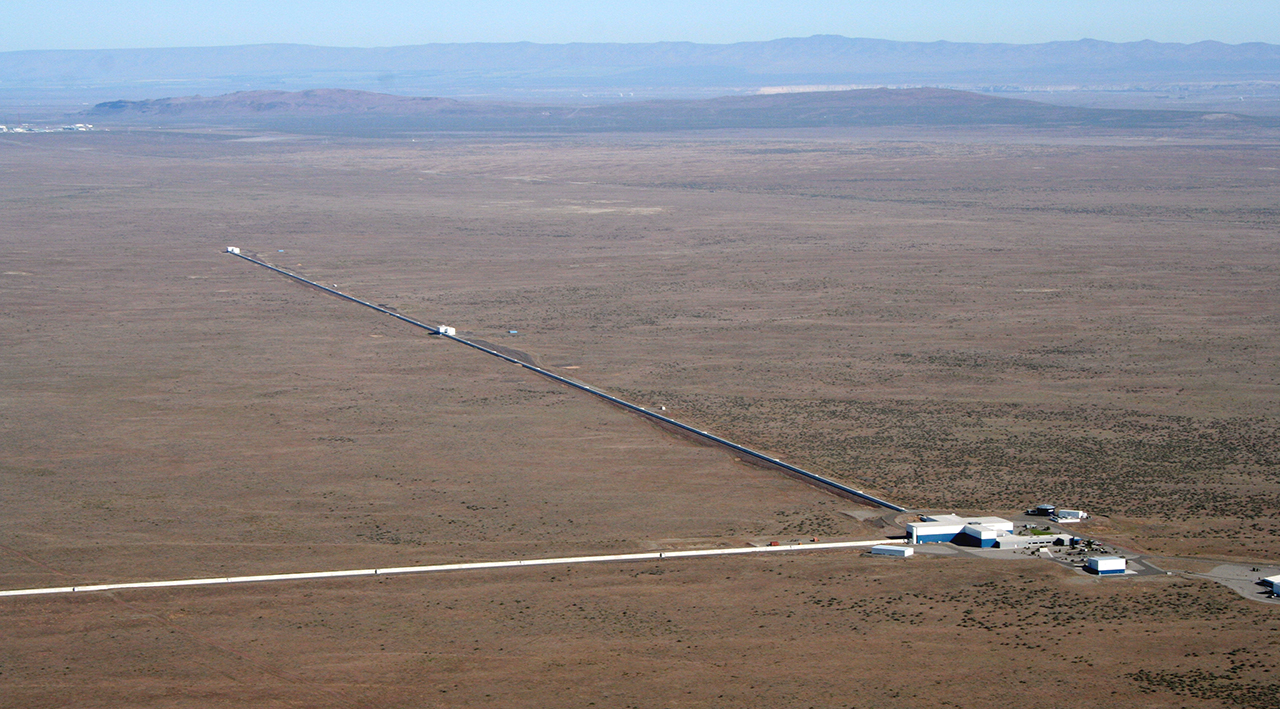

The LIGO Laboratory operates two detector sites, one near Hanford in eastern Washington, and another near Livingston, Louisiana. This photo shows the Hanford detector site with its twin 4.3 km (2.5 mi.) long laser interferometers. Photo courtesy of Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab.

This spring semester, Missouri S&T became the state’s only institution to join the worldwide LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory) Scientific Collaboration (LSC) of researchers committed to detecting cosmic gravitational waves. This research explores the fundamental physics of gravity using the emerging field of gravitational wave science as a tool for astronomical discovery.

Joining the LSC makes S&T part of a collaboration of about 1,300 scientists from 18 countries and over 100 institutions dedicated to detecting the gravitational waves predicted in Albert Einstein’s 1915 general theory of relativity. In 2015, 100 years later, Einstein’s theory was confirmed when LIGO and Virgo, its European observatory partner located in Pisa, Italy, first detected gravitational waves from a cataclysmic event in space during Advanced LIGO’s inaugural observing run. With its twin, 4-kilometer-long laser interferometers located in Hanford, Washington, and Livingston, Louisiana, the LSC experiment detected a feeble signal that originated 1.3 billion years ago when two black holes collided.

On April 25, 2019, on its third observational run, LIGO and Virgo registered gravitational waves from what appears to be a crash between two neutron stars — the dense remnants of massive stars that previously exploded. The next day, on April 26, the LIGO-Virgo network spotted another candidate source that may have resulted from the collision of a neutron star and a black hole, an event never before witnessed. Read more about this event in LIGO CalTech’s May 2 news release.

Dr. Marco Cavaglia, S&T physics professor and co-chair of the LSC Burst Sources Working Group. Photo by Tom Wagner/Missouri S&T ©2019 Missouri S&T All Rights Reserved.

These are exciting times for Dr. Marco Cavaglia, professor of physics at S&T and an expert in gravitational physics and multimessenger astrophysics, a new research field that began in 2017 with the first observation of a two-neutron-star merger. Multimessenger physicists study data from gravitational waves, electromagnetic waves and high-energy particles like neutrinos and cosmic rays to make astronomical discoveries about the universe.

“Space is the frontier of our exploration,” says Cavaglia, “and the LSC is at the forefront of astrophysics research — it is one of the largest, most ambitious projects ever funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF).”

Cavaglia joined S&T in January from the University of Mississippi. He has been an active researcher and leader in the LSC for over 10 years, serving as the organization’s assistant spokesperson from 2012 to 2017 and previously as founding chair of its diversity and public education and outreach groups.

Cavaglia now co-chairs LIGO’s Burst Sources Working Group, an LSC team of over 200 researchers from across the world that look for various gravitational-wave signals with no assumption of their origin or form.

The LIGO Laboratory detector site near Livingston, Louisiana. Photo courtesy of Caltech/MIT/LIGO Laboratory.

“This search is different from looking for signals like colliding black holes that can be modelled precisely using Einstein’s theory of general relativity,” says Cavaglia. “We’re looking for signals of various duration, as well as gravitational waves that originated in stellar explosions or even cosmic strings. While gravitational waves from these sources have not been detected yet, their detection would provide invaluable information about the origin and dynamics of these cosmic events.”

With a grant from the NSF, Cavaglia plans to continue his LSC work in the physics department at S&T. A newly formed astrophysics research group will have a lab that will include a remote control room for the LIGO detectors. The group will advance the LSC’s work with data analysis, detector characterization and educational and public outreach.

Missouri S&T’s LIGO group includes:

— Evan Goetz, a post-doctoral researcher and LSC member joining from the California Institute of Technology

— Ryan Quitzow-James, a post-doctoral researcher and LSC member joining from the University of Oregon

— Doctoral students Kentaro Mogushi and Dripta Bhattacharjee joining from the University of Mississippi and Yanyan Zheng, from Missouri S&T.

“Our research activities will follow in the footsteps of my previous work in the areas of instrumentation, astrophysics and service to the LIGO collaboration that were critical for the detections of the gravitational wave signals,” says Cavaglia.

“We’re already seeing hints of the first observation of a black hole swallowing a neutron star,” says David H. Reitze of Caltech, Executive Director of LIGO. “If it holds up, this would be a trifecta for LIGO and Virgo — in three years, we’ll have observed every type of black hole and neutron star collision. But we’ve learned that claims of detections require a tremendous amount of painstaking work — checking and rechecking — so we’ll have to see where the data takes us.”

“The hunt for the dark side of the universe is on,” says Cavaglia.

LIGO is funded by NSF and operated by Caltech and MIT, which conceived of LIGO and led the Initial and Advanced LIGO projects. Financial support for the Advanced LIGO project was led by the NSF with Germany (Max Planck Society), the U.K. (Science and Technology Facilities Council) and Australia (Australian Research Council-OzGrav) making significant commitments and contributions to the project. Approximately 1,300 scientists from around the world participate in the effort through the LIGO Scientific Collaboration, which includes the GEO Collaboration. A list of additional partners is available at my.ligo.org/census.php.

The Virgo Collaboration is currently composed of approximately 350 scientists, engineers, and technicians from about 70 institutes from Belgium, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, and Spain. The European Gravitational Observatory (EGO) hosts the Virgo detector near Pisa in Italy, and is funded by Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) in France, the Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare (INFN) in Italy, and Nikhef in the Netherlands.

A list of the Virgo Collaboration members can be found at public.virgo-gw.eu/the-virgo-collaboration. More information is available on the Virgo website at www.virgo-gw.eu.

Leave a Reply