Missouri S&T professor’s book uncovers the origin of ‘jazz’

Posted by Peter Ehrhard

A new book written by a Missouri University of Science and Technology researcher explores how the term “jazz” became a common word in the English language. The book is a result of over 25 years of research on the subject.

A new book written by a Missouri University of Science and Technology researcher explores how the term “jazz” became a common word in the English language. The book is a result of over 25 years of research on the subject.

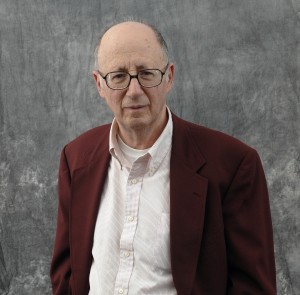

Dr. Gerald Cohen, professor of foreign languages at Missouri S&T, self-published the book titled “Origin of the Term ‘Jazz.’” In the book, he contends that the phrase had its origins in the 1910s. Cohen supports the view that E.T. “Scoop” Gleeson, a sports writer for “The San Francisco Bulletin” newspaper, brought the term into common usage from obscurity.

On March 6, 1913, Gleeson used the term “jazz” to mean pep, vim, vigor and fighting spirit in an effort to inspire a local minor-league baseball team. Cohen says the team didn’t look good on paper, but Gleeson repeatedly asserted they had the “jazz,” and he expected that this “jazz” would bring them victory. Two years later, the term was brought to Chicago to denote a musical genre.

“The subject is filled with controversy as there are innumerable suggestions about how the term ‘jazz’ arose,” says Cohen. “Most of them can be set aside once we see that ‘jazz’ was a baseball term in 1913 in San Francisco, before being transferred to music, which was first attested in Chicago, 1915.”

Cohen’s findings on the word’s origin also include definitions, such as its sexual meaning. Cohen cites Wynton Marsalis’ statement in the Ken Burns film “Jazz,” and the fact that the musical use of the term is frequently said to derive from this meaning.

He also found that, despite the common belief that the term formed from African-American musicians performing in the genre, some of the early jazz musicians disliked the term. Jazz great Sydney Bechet, for example, wrote in 1960, “But let me tell you one thing: Jazz, that’s a name white people have given to the music.”

Cohen is printing only 80 copies. He says he will rely on reviews in scholarly journals to verify the book’s scholarly worth, due to its self-published status. The soft-bound book is 193 pages long and costs $25, plus $10 mailing costs. For more information or to order a copy of the book, email Cohen at gcohen@mst.edu.

I have found usages of jazz to refer to music that pre-date the baseball articles. George Morrison, a musician born in Fayette, Missouri, heard it in 1911 and painted it on the side of his car to describe the music that his band played (Gunther Schuller interview). A New Orleans trumpet player used it in 1912 as reported by Samuel Charters. Wilbur Sweatman (born in 1882) claimed he invented jazz in the Ozarks of Missouri. I am the author of “Kansas City Jazz: A Little Evil Will Do You Good” (Equinox Publishing, 2023) and other books on jazz.

Thank you for your research Dr Cohen – 25 years is a long time to track down a word!

I have been doing a bit of research as well (I am a documentary filmmaker and a jazz drummer) for my next film on women in jazz and have come across a few things to add to your research.

The first is giving you credit where due: shortly after you published your book you sent info to Lewis Porter aiding him in his research which set as April 12, 1912 as the first published appearance of the word “jazz”. Porter writes:

“Ben’s Jazz Curve,” Los Angeles Times, April 2, 1912.

“Jazz” seems to have originated among white Americans, and the earliest printed uses are in California baseball writing, where it means “lively, energetic.” (The word still carries this meaning, as in “Let’s jazz this up!”) The earliest known usage occurs on April 2, 1912, in an article discovered by researcher George A. Thompson, and sent to me courtesy of Dr. Cohen.

The page is hard to read, so I have retyped the text, with clarifying comments [in brackets]:

BEN’S JAZZ CURVE. “I got a new curve this year,” softly murmured Henderson yesterday, “and I’m goin’ to pitch one or two of them tomorrow. I call it the Jazz ball because it wobbles and you simply can’t do anything with it.” [That is, it’s too lively for them to hit it.] As prize fighters who invent new punches are always the first to get their’s Ben will probably be lucky if some guy don’t hit that new Jazzer ball a mile today. It is to be hoped that some unintelligent compositor does not spell that the Jag ball. That’s what it must be at that if it wobbles. [That is, he jokes, don’t confuse this with a drunken “jag.”]

Please also notice that in this very first printed use of the word, it is spelled “jazz.”

=====

My second note is more for Peter Earhard (as I have not read Dr Cohen’s book to know whether he makes the same claim/inference): Sidney Bechet does not actually say he dislikes the word “jazz” in his book Treat It Gentle and I believe your attempt to identify Bechet as one of the musicians who dislike the word is incorrect. Sidney, in his book, follows the statement, jazz is “… a name white people have given to the music,” with, “…it does not explain the music.” There is no anger or dislike expressed over the word, but he proceeds to explain that he uses the word “ragtime” or “rag time” to show how there is “a spirit right in the word.”

Additionally, Bechet did not actually write those words in 1960. He spoke them into a tape recorder, before he died in 1959, that was then transcribed, and published posthumously in 1960.

I believe now, that spirit does exist in the word jazz, and it most certainly has for many decades at least if one were to only use Art Blakey as an example having named his own group Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers.

I cover many elements of jazz history, live performance, and the economics of gigging as a jazz musician in my documentary films “JazzTown” (AppleTV, Amazon Prime…) and “Who Killed Jazz” (Vimeo).

I have found a number of uses from New Orleans and the midwest of the term “jazz” that predate the 1913 California baseball article. See the following article from “All About Jazz.”

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/which-came-first-jazz-or-baseball

I have found other earlier cites going through interviews of Roy J. Carew, born in 1875, who moved to New Orleans in 1903.