‘Fake news’ from 1738 offers lessons for modern historians, says Missouri S&T scholar

Posted by Andrew Careaga

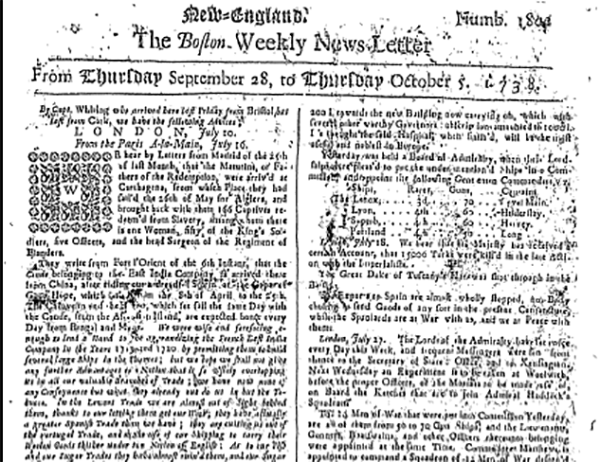

Top of the front page of the Sept. 28, 1738, issue of the Boston News-Letter, which carried a false news story about a supposed Native American uprising on Nantucket Island.

A widely circulated 1738 newspaper account of a Native American uprising against British settlers on the New England island of Nantucket – a report that turned out to be false – offers important lessons for historians today, says an assistant professor at Missouri University of Science and Technology.

This 18th-century version of fake news, first reported in the Boston News-Letter on Sept. 28, 1738, is the subject of a recent journal article by Dr. Justin Pope, an assistant professor of history and political science at Missouri S&T who specializes in colonial American history.

Dr. Justin Pope, assistant professor of history Sam O’Keefe/Missouri S&T

Pope’s article, “Inventing an Indian Slave Conspiracy on Nantucket, 1738,” was published in the Summer 2017 edition of the journal Early American Studies. In it, he describes a colonial America that was fertile ground for such false and sensationalized news reports. New England in particular was teeming with newspapers that had an intense interest in sharing stories of slave unrest in the Americas, he writes. That, along with British colonists’ fears of Native Americans and a growing appetite in England for what one British newspaper called the “furious itch of Novelty,” created conditions favorable for the bogus news report.

The “Nantucket conspiracy,” as Pope calls it, is also a cautionary tale for historians who rely on newspaper reports for their accounts of life in colonial America, Pope says.

“The Nantucket conspiracy serves as a warning to all of us who rely on these printed stories,” Pope writes in the journal article. “It illuminates how early American printers transformed the fearful rumors of colonists into sensational news and, in the process, created conventions for reporting slave unrest during a formative period in the history of the early American press.”

The 1738 newspaper story began as a rumor that “would have passed into local lore if not for the newspaper men of Boston,” writes Pope. It began with printer John Draper, who first reported the account in his Boston News-Letter on Sept. 28, 1738.

“Draper fashioned an account of the Nantucket conspiracy that depicted an imminent rebellion” by members of the Wampanoag tribe, who co-existed on Nantucket with British settlers, Pope writes. Draper wrote that the rebellion was prevented by “one good Indian fellow” who betrayed his fellow plotters.

Going viral, colonial-style

Relying on anonymous sources – “We hear from Nantucket,” Draper’s account begins – the Boston News-Letter story “took off,” Pope writes. Newspapers on both sides of the Atlantic ran with the story, which soon became the 18th century equivalent of a viral social media post. “Draper’s story made for good copy,” Pope adds.

“Within a week, his rivals in Boston had copied his version of the conspiracy verbatim,” writes Pope. Within two weeks, printers John Peter Zenger in New York City and Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia were running the story.

“Over the course of the next three months, British sailors and printers spread Draper’s report of an impending uprising on Nantucket … to newspapers in London and the British Isles,” Pope writes.

One week after reprinting Draper’s original article, the Boston Gazette, a rival of Draper’s publication, printed a retraction following a Nantucket sailor’s challenge of Draper’s version. Nevertheless, Draper’s fabricated story marched forward on both side of the Atlantic.

The false account even made its way into some history books, Pope writes. Nearly a century after the false story was debunked, historian Obed Macy, in his book The History of Nantucket, mentions the Wampanoags as “so bold as to threaten the English with total annihilation,” and in the 1878 book History of the American Whale Fishery, Alexander Starbuck “relied on Draper’s article to remember ‘the Indian plot’ on Nantucket,” Pope writes.

Even as recently as 2000, historians Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker “incorporated the newspaper’s account of the conspiracy into their list of Atlantic-wide insurrections of the 1730s.”

A cautionary tale

Even though the Nantucket conspiracy story was “an invention,” Pope cautions fellow historians from taking newspaper reports from the era at face value.

“Historians must always be careful with their use of evidence,” Pope says. “Newspaper reports from colonial America are especially challenging because printers had few journalistic standards and no concern about plagiarism. English printers found it perfectly acceptable to copy any account of interest to readers.”

Pope chose to write about the incident because “I wanted to study the path of ‘fake news,’ to understand how a false conspiracy scare on a small island in New England became big news and even historical evidence for generations of historians,” he says.

The Nantucket conspiracy wasn’t the final or most egregious false report on record. In 1741, three years after the Nantucket incident, New Yok City papers sensationalized trials of a trumped-up plot “to set the city on fire in preparation for a Spanish invasion,” he says. Although the key witness, a young white servant girl, changed her story several times, New York officials ended up hanging or burning 34 people.

“Printers published dozens of stories about the New York City trials that sensationalized every accusation made against the accused people without concern for their denials of any guilt,” Pope says.

“Historians have considered the New York City conspiracy a tragedy for a long time, but have little evidence outside the trial record and these newspaper reports,” says Pope. “One of my goals with the study of the Nantucket conspiracy was to show there were definitely false conspiracy reports circulating in the colonies prior to the 1741 New York conspiracy.”

Pope is also the author of the forthcoming book Dangerous Spirit of Liberty: How Slave Rebellion Transformed the Atlantic World, 1688 to 1750, which is under review with editors of the Atlantic Slavery Series of Cambridge University Press. At Missouri S&T, he teaches early American history.

Leave a Reply