A conversation on race

Posted by Andrew Careaga

Anthony Yemitan at the 2018 Black History Month kickoff event in the Havener Center Atrium. Sam O’Keefe/Missouri S&T

This is the first in a series of articles about campus climate issues that were brought to light by the university’s campus climate survey, the results of which were presented in September 2017. (Note: This article was substantially revised on March 1, 2018.)

Fifty years after the assassination of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. and nearly a decade since the United States elected its first black president, racism continues to be a concern in America and on its college campuses.

A recent study by the Anti-Defamation League, released at the end of January, found that white-supremacist propaganda at colleges increased by 258 percent from the fall of 2016 to the fall of 2017 and affected 216 college campuses across the U.S.

Eleven Missouri S&T students talk about their struggles, goals and being minorities in the STEM fields in interviews highlighting Black History Month.

Not all forms of racism are as extreme as white supremacist activity, however. For students of color at Missouri S&T, racism can take many forms, from a recent social media post by a Missouri S&T student that contained racist and homophobic slurs to more subtle customs, often called microaggressions, and even the nature of the university itself. At a PWI (predominantly white institution) like Missouri S&T, a black student may often be the only person of color in a class. If that student is also a woman, then she is often both the only black and only female in the class.

Then there are the seemingly trivial obstacles black students face.

“One of the biggest questions we hear” on a GroupMe frequented by S&T African American students “is, ‘Where can I get my hair cut?’” says Ravon Lingard, a junior in engineering management from St. Louis.

Like many of her fellow black female students at S&T, Lingard travels to St. Louis for her hair appointments. Many black male students travel 30 minutes west to St. Robert, she adds.

And if students get a craving for soul food, there’s no local restaurant that specializes in such dishes.

Dealing with microaggressions

Jimmie Washington, a sophomore chemical engineering major from Houston, Texas, has experienced more than a few microaggressions during his time at S&T. During his freshman year, Washington says his chemistry recitation partner would not speak to him or work with him on assignments, even though Washington tried to connect with the student. Even when his classmate asked for help from the teaching assistant, and the TA suggested he talk to Washington, the student refused.

So Washington withdrew.

“I just started wearing my headphones” to recitation, Washington says. “I would just put on some gospel music and do my work.”

Lingard has also experienced her share of microaggressions, especially from students who assume she is at S&T as a student-athlete.

“I’ve had a lot of people ask me if I’m on the track team,” says Lingard, who is president of the university’s National Society for Black Engineers chapter. “I’ve never even been to the track here. I’ve never even been to the gym.”

These types of situations are more pervasive than overt racist behavior, S&T students of color say.

Washington, who is on the track team (he’s a hurdler), says the transition from the big and diverse metropolis of Houston to the small town of Rolla was “a culture shock, but it wasn’t so much that I couldn’t handle it.” he says. “I came here because I wanted to try something new. So far, it’s helped me more than hindered me.”

Life at a PWI

A 2016 campus climate survey found that 18 percent of the S&T community experienced some sort of exclusionary behavior

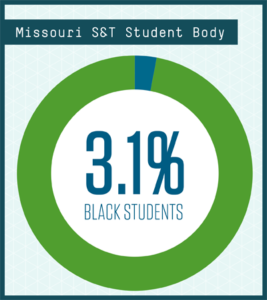

Last fall, Missouri S&T’s 279 black students made up 3.1 percent of the student body. Overall, underrepresented minorities make up 9.6 percent of the student body.

A study of the university’s climate, conducted in 2016, found that 18 percent of the campus community – students as well as faculty and staff – had experienced some sort of exclusionary behavior, whether related to race or ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, military status, faculty or staff status, or other characteristics. That’s an increase from 14 percent who reported similar experiences through a climate survey conducted in 2012, and that change is one indicator that Missouri S&T has room to improve in terms of creating a welcoming environment.

Missouri S&T is not alone in this regard. The latest climate survey findings “were consistent with those found in higher education institutions across the country,” wrote Rankin & Associates, the firm that conducted the research.

Four overarching themes emerged from the survey. Topping the list was “inclusion-related concerns.” In the final report, the research firm points out, “Disregard for current diversity related initiatives was emphatically noted by student respondents who elaborated on their opinions of Missouri S&T’s institutional initiatives.”

The findings come from a 2016 report, when the university’s diversity, inclusion and equity programs were organized differently. More recently, black student leaders spoke highly of the student diversity initiatives staff’s timely and positive response to the recent racist social media post.

Being the ‘Black ambassadors’

Black students make up 3.1 percent of the Missouri S&T student body

Lingard, Washington and other African American student leaders sometimes feel an obligation to, in Washington’s words, “be the black ambassadors” to the S&T community. Washington sometimes feels as though he is supposed to articulate the views and perspectives of all African Americans to his fellow students — to be the spokesperson for black culture — and he doesn’t think it’s fair to expect a single black student to speak for all black people, any more than a white student should be expected to explain why country music is so popular or the appeal of Donald Trump.

Washington wants campus leaders to understand that not all black students want to take on that role. Most are here to get an outstanding education, but they want to do so in an environment that is inclusive and welcoming.

They also want an environment where they can discuss topical issues – even issues beyond race. Alyse Rogers, a senior chemical engineering major from Lake Saint Louis, Missouri, sees the Black Man’s Think Tank organization as one that can stimulate thinking and conversation about difficult topics. Rogers is president of that organization, which hosts “intriguing and engaging discussions” on a wide range of topics, including gender issues, “colorism,” technology’s impact on students and society, and the military’s previous ban on transgender people to enter the service.

“We want to encourage students to feel comfortable enough to have an intellectual conversation with people of diverse backgrounds, experiences and viewpoints,” she says. “When someone attends a BMTT discussion, they can expect their thoughts and perspectives to be welcomed with respect and open minds, regardless of whether others agree or disagree.”

Such conversations in society can be difficult, “because someone may disagree and make it known in an unpleasant and unwelcoming way,” Rogers says. Yet she, Lingard and Washington agree that these conversations are needed and important to help Missouri S&T become more welcoming and inclusive to all.

Ideally, Washington says, Missouri S&T would become a place where students “understand our differences and celebrate our differences at the same time.”

How you can get involved

What can you do to help make Missouri S&T a more inclusive environment?

- Learn from each other. Take advantage of the many cultural educational opportunities on campus, from Black Man’s Think Tank discussions to International Students Day (March 4), Women’s History Month (activities throughout March) and other events. Visit the Missouri S&T Calendar of Events for a listing of activities.

- Visit 605 W. 11th St. That’s the street address for the university’s student diversity initiatives office, which supports diversity-related programming and provides space for many student organizations. Drop by to visit with the staff and fellow students.

- Help shape the future of campus. Attend a meeting of the Chancellor’s Committee for Diversity and Inclusion, which is a campuswide group committed to making Missouri S&T a more inclusive campus. To learn more, contact Neil Outar, interim chief diversity officer, at naoutar@mst.edu.

- See something, say something. If you witness or experience any act that you believe may discriminate, stereotype, harass or exclude anyone based on some part of your or their identity, report it.

African/African Americans should get involved in student organizations, and voice their concerns.

Andrew, thanks for persisting, as the struggle continues.