Researchers show how green slime could help save the world

Posted by

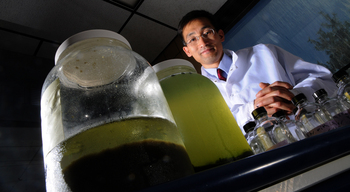

Several glass containers filled with algae-stained water sit on a table in Dr. Paul Nam’s laboratory at Missouri University of Science and Technology. Next to the big green bottles are two much smaller vials. One of the vials, labeled “biodiesel,” contains a mostly clear solution. Nam picks up the other vial, labeled “algae oil,” and gives it a shake. A small amount of dark liquid swishes around.

At first, the amount of potential fuel in these little vials doesn’t seem too impressive. But Nam says algae could play a big role in the unfolding dramas associated with finding alternative sources of energy and reducing greenhouse gasses.

At first, the amount of potential fuel in these little vials doesn’t seem too impressive. But Nam says algae could play a big role in the unfolding dramas associated with finding alternative sources of energy and reducing greenhouse gasses.

Nam, who has spent much of his career studying the versatile uses for soybeans, says algae could be the next big thing. He points to a study by the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory as evidence. The study showed that algae, if we think of it as a crop, is capable of yielding up to 10,000 gallons of oil per acre on an annual basis. By way of contrast, corn yields 18 gallons per acre and soybeans yield 48 gallons per acre.

“There are three main problems facing the world,” says Nam, an assistant professor of chemistry at Missouri S&T. “We have a food shortage, a fuel shortage, and a need to curb pollution.”

Nam thinks algae could help address all three concerns. If more fuel were produced from algae, then more corn and soybeans could be grown for food. And the Earth-friendly attributes of algae make it even more intriguing. Algae consume carbon dioxide and can be grown in wastewater. This means they can be used to take some pollution out of the air and water.

That is exactly what Nam and some colleagues from various universities are doing at a coal-fired power plant in Chamois, Mo. The research team is cultivating algae in five 2,500-gallon pools that are located at the plant. The algae literally take some of the carbon dioxide emissions from the plant’s smokestack.

“So we are recycling carbon dioxide and we are also interested in turning the algae biomass into biofuels,” Nam says.

The research team is using strains of algae native to Missouri. Unlike macro-algae (seaweed), these-strains are microscopic. They don’t become visible until they have multiplied many times. But, as those who are familiar with algae-infested ponds know, the rate of reproduction is very fast.

One of the problems Nam is currently working on has to do with removing the water from the algae in order to then extract the oil. The oil content in algae makes it float, but Nam has developed a method to encourage the slimy stuff settle to the bottom of a water-filled container.

Once the oil has been extracted for biodiesel, the defatted algae are mainly carbohydrates and protein that can be used for ethanol production and animal feed, respectively. “By making as many products as you can from one source, you can off-set costs,” he says.

Several Missouri S&T researchers are studying algae, including one professor who is trying to grow it in an underground mine. Among the collaborators in Nam’s group are Dr. Keesoo Lee, associate professor of microbiology at Lincoln University; Dr. Virgil Flanigan, director of the Center for Environmental Science and Technology at S&T; and Dr. Fabio Rindi, algae systematist at the National University of Ireland.

The collaborative project, “Integrated program for the development of microalgae as sustainable resources for biofuels and biomaterials,” has been funded in the amount of $527,000 by the Missouri Life Sciences Research Board.

Associated Electric Cooperative Inc., the Central Electric Power Cooperative and Lincoln University are also supporting Nam’s carbon sequestration project. The Associated Press has reported on additional details of the collaborative research effort.