NSF grant helps UMR researcher with post-Katrina study

Posted by news

Sixteen months after flooding and power loss – brought on by Hurricane Katrina – knocked out key telecommunications hubs along the Gulf Coast, a University of Missouri-Rolla researcher has developed a truly mobile solution to the communication problem.

Cellular and land-based phones both rely on a fixed physical infrastructure. In New Orleans, hurricane winds and flood waters from Lake Pontchartrain hindered rescue efforts by crumpling communication towers and knocking out power to many primary controllers and cell sites. Recovery efforts then slowed as police, fire and rescue personnel struggled to work together after the telecommunications network in Mississippi, Louisiana and Alabama was extensively damaged.

The new communication system uses a network of tiny, wireless devices and a dynamic programming-based protocol to provide first responders with the communication tools they need to plan a coordinated, effective response, says Dr. Jagannathan Sarangapani, professor of electrical and computer engineering at UMR.

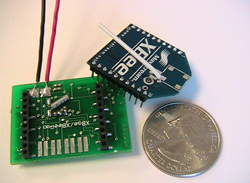

The devices, called motes, are installed with wireless communications and use sensors to detect a myriad of variables from the environment. Developed to be deployed on emergency vehicles, the motes then pass this limited information to other nearby UMR motes in a high-tech version of a children’s telephone game, except the original and final messages are identical.

“If a sufficient number of motes with UMR communication networking protocols are deployed on emergency vehicles, then communication is not an issue and is available in real time: 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” Sarangapani says. “No fixed infrastructure is used for communication and therefore it’s reliable.”

|

| The UMR-developed motes are smaller than a quarter. |

Currently available protocols do not guarantee that a route can be found. The UMR-developed protocol ensures that the message would find the shortest path to its base. It does this by trying to minimize the cost metric – energy multiplied by delay and divided by distance.

“The UMR motes use broadcast mechanism and neighbor discovery to identify relay nodes, which could be mobile, to the basestation,” Sarangapani explains. “Thus communication is not dependent upon any fixed infrastructure. Using the relay nodes, the information is passed around.”

In addition to providing a means of getting information to decision makers, the UMR-developed motes and protocol could be used to monitor civil infrastructure, perimeters and other structures, like levees. Traditional maintenance practices of “fail and fix” could be transformed into a “predict and prevent” methodology, Sarangapani adds.

The research is supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation’s Small Grant for Exploratory Research (SGER) program. NSF funds projects through its SGER program “to support fundamental science and engineering projects whose results may enable our country to better mitigate, prepare for, respond to, and recover from catastrophic events.”

The research project is one of a handful of projects being worked on at UMR’s Center Site on Intelligent Maintenance Systems, recently established by the National Science Foundation as part of NSF’s Industry/University Collaborative Research Center program. The new center focuses on enabling products and systems to achieve and sustain near-zero breakdown performance.